Ambitions of a New Era

How the Constraints of the Old Political Order Still Bind Zohran... for now

“I’m not going to stop the wheel. I’m going to break the wheel” - Daenerys Targaryen

In the first general election debate, Zohran Mamdani named FDR his favorite modern president. Cuomo and Sliwa chided him for considering him “modern,” but that was the point; no president has met Mamdani’s standards for more than eighty years. He is not interested in being Obama or Clinton, an incrementalist reformer with significant accomplishments, but ultimately operating within the boundaries of the machine that precedes him. He wants to fundamentally change the way the government works. He wants to usher in a new “Era”, that will last decades beyond his administration, where his successors are forced to play by the new rules that he will write.

Mamdani made this clear last Tuesday. “For as long as we can remember,” he told the rapturous crowd at Brooklyn Paramount on election night, “the working people of New York have been told by the wealthy and the well-connected that power does not belong in their hands… Tonight, against all odds, we have grasped it. The future is in our hands.” Mamdani is 34 years old; so is his chief of staff and primary campaign manager Elle Bisgaard-Church, his speechwriter Julian Gerson is 29, his lead strategist Morris Katz is 28, and most of his ninety-thousand strong volunteer army is even younger. “How long they can remember” is an open question. But they can remember the eight-year mayoralty of progressive “Tale of Two Cities” redistributionist Bill de Blasio, and they do not remember it as a time when power was in the right hands. They don’t want to be de Blasio 2.0.

Instead, as Mason B. Williams wrote in Vital City, Mamdani’s speech points to the ambitions of New Deal-era mayor Fiorello La Guardia, who sought to wield government as a tool that could improve every facet of a working New Yorker’s life. Williams describes the sprawling public works of La Guardia’s mayoralty: “New parks and playgrounds; theater and opera accessible to all; decent, affordable housing; monumental new swimming pools — these were not only goods and services, but gestures to working-class New Yorkers that the city cared about the quality of urban life in the broadest sense.”

Williams then chronicles the end of this era of ambition in the 1960s and 1970s, with the rise of racial tensions and the collapse of the city’s economic model, and the struggles and ultimate failures of two progressive mayors, David Dinkins and Bill de Blasio, to revive La Guardia’s spirit. While both accomplished significant achievements in their tenure, neither succeeded in breaking out of their government’s neoliberal constraints. With tax rates basically anchored in place by popular demand, both could raise new revenue only by growing the value of private real estate, by convincing wealthy people and profitable corporations to move here, or by holding out a begging bowl to hostile, moderate governors named Cuomo. And both governed utterly at the mercy of the crime issue. No matter how forcefully they repeated common tough-on-crime aphorisms (“I intend to be the toughest mayor on crime this city has ever seen”), no matter how many times they appointed reactionary broken-windows police chiefs like Raymond Kelly and William Bratton, they were completely vulnerable on this issue. They could not weather any increase in any kind of crime, or get into any kind of conflict with the police union, without suffering disastrous political consequences.

Williams ends his piece on an optimistic note. This time might be different, he writes, because whereas de Blasio and Dinkins were “reactive” figures, Mamdani “has created a genuinely new political force in the city.” Michael Lange sketched out what this force looks like electorally in his piece yesterday (ironically, or perhaps ominously headlined “The Rainbow Coalition,” a direct Dinkins callback): “The core tenants of Mamdani’s coalition are the city’s most ascendant demographics: young voters, the college-educated renter class, South Asians, and Muslims,” while Cuomo’s coalition represents “the last gasp of the Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg coalition, arrangements that once reigned municipal politics.”

When I started writing about this race in March, I (like everyone else) assumed those arrangements still reigned. The 2021 mayoral election had cleaved the city into two coalitions, roughly equal in population. There was the Eric Adams coalition, the outer-borough blocs of aging, car-reliant homeowners, a multiracial coalition dominated by majority-Black neighborhoods of the Bronx, Southeast Queens, and Flatbush and Brownsville in Brooklyn. And there was the Kathryn Garcia coalition, powered by the well-educated elites of Manhattan and Brownstone Brooklyn. Cuomo, I wrote, began his campaign in a dominant position because he had the potential to win both coalitions. The Adams voters were Cuomo’s dead-end, most loyal supporters in his darkest moments as governor, and they were his exclusively, no other candidate had made any progress with them. And while the Garcia coalition might have a few liberals and anti-corruption Cuomo-skeptics, it also had plenty of loyal New York Times readers who still vividly remembered his covid-era hagiography. There was also a third group; the young, disaffected, DSA-curious transplants of Greenpoint and Astoria. But as loud as they were on Twitter, this group, everyone agreed, did not turn out to vote much. So Cuomo was a heavy favorite. Perhaps a candidate like Adrienne Adams could squeeze Cuomo by eating into his margins in her native Southeast Queens; under the “arrangements that once reigned municipal politics,” this was his only real threat.

Mamdani overthrew these arrangements by creating his own electorate. That third group became the fearsome “Commie Corridor,” where he could recruit tens of thousands of frenzied volunteers, achieve 100% turnout increases and bank absurd 85-15 margins. The Garcia coalition of educated elites turned out to be far hungrier for a fresh, energetic, handsome face than previously imagined. These two developments are remarkable and have been widely discussed in elite media, which is dominated by Garcia coalition writers and editors with Commie Corridor children.

There were two other achievements, which were emphasized less, but just as essential. Firstly, Mamdani was able to splinter the Adams coalition by picking off the blocs that Lange mentions: South Asian immigrants, Muslims, and to a lesser extent, Hispanics. He lost precincts in Black strongholds in the Bronx by 20 and in Flatbush by 30 or more, but he had built up enough outer-borough support elsewhere to weather that. And secondly, he ran about five points better than expected just about everywhere. He had generated enough enthusiasm, and his ground-game advantage proved so dominant that if he was supposed to lose a neighborhood by twenty-five points, he tightened it to twenty, all over the city. These last two steps–splintering the outer-borough blocs and dominating ground game everywhere– enabled Mamdani to overthrow the “arrangements that once reigned municipal politics.” Specifically, he became the first Democratic nominee for mayor to win the primary (by thirteen points!), without the support of either the Upper East Side or the vote-rich, outer-borough Black neighborhoods.

This is the formula for a generational, era-defining political realignment. If you win by enough, with a new group of supporters, you don’t have to listen when the old groups tell you not to do something. It’s a map that filled me with hope that a new dawn of transit-oriented urbanism might be on the horizon. And it’s a map that might allow for the old rules around spending limits and crime policy to be loosened a bit. The old rules, I wrote, might say that if the governor, city’s business elites, and the rank-and-file police officers all insist that Mamdani keep Jessica Tisch on as NYPD commissioner, then he has no choice. But after this wave realignment election, there might be another way, especially if Mamdani was more popular than Hochul downstate, if the city’s business elites were not an essential part of Mamdani’s majority coalition, and if officers were telling Brad Lander that they liked Zohran even as they assisted ICE agents dragging Lander down the hallway of 26 Federal Plaza. Under the new rules, maybe he could pick someone he liked more.

Two weeks before Election Day, Mamdani decided that in this particular respect, the old rules still apply, announcing that he planned to keep Tisch. The next day, he went onstage with Hell Gate reporters and grimly defended Tisch’s record of opposing bail and discovery reform, protecting the discriminatory “gang database,” continuing to use the liability-generating Strategic Response Group, and flaunting CCRB recommendations. It will be different when he is her mayor, he told the crowd. “Everyone will follow my lead. I’ll be the mayor.” Since then, Tisch has publicly praised outgoing Mayor Eric Adams’s call to hire 5,000 new officers, directly contradicting Mamdani’s position that the size of the force is good as is. She still has not confirmed that she will accept the appointment. Every day she waits, she makes it more clear that it is her decision, not the incoming mayor’s.

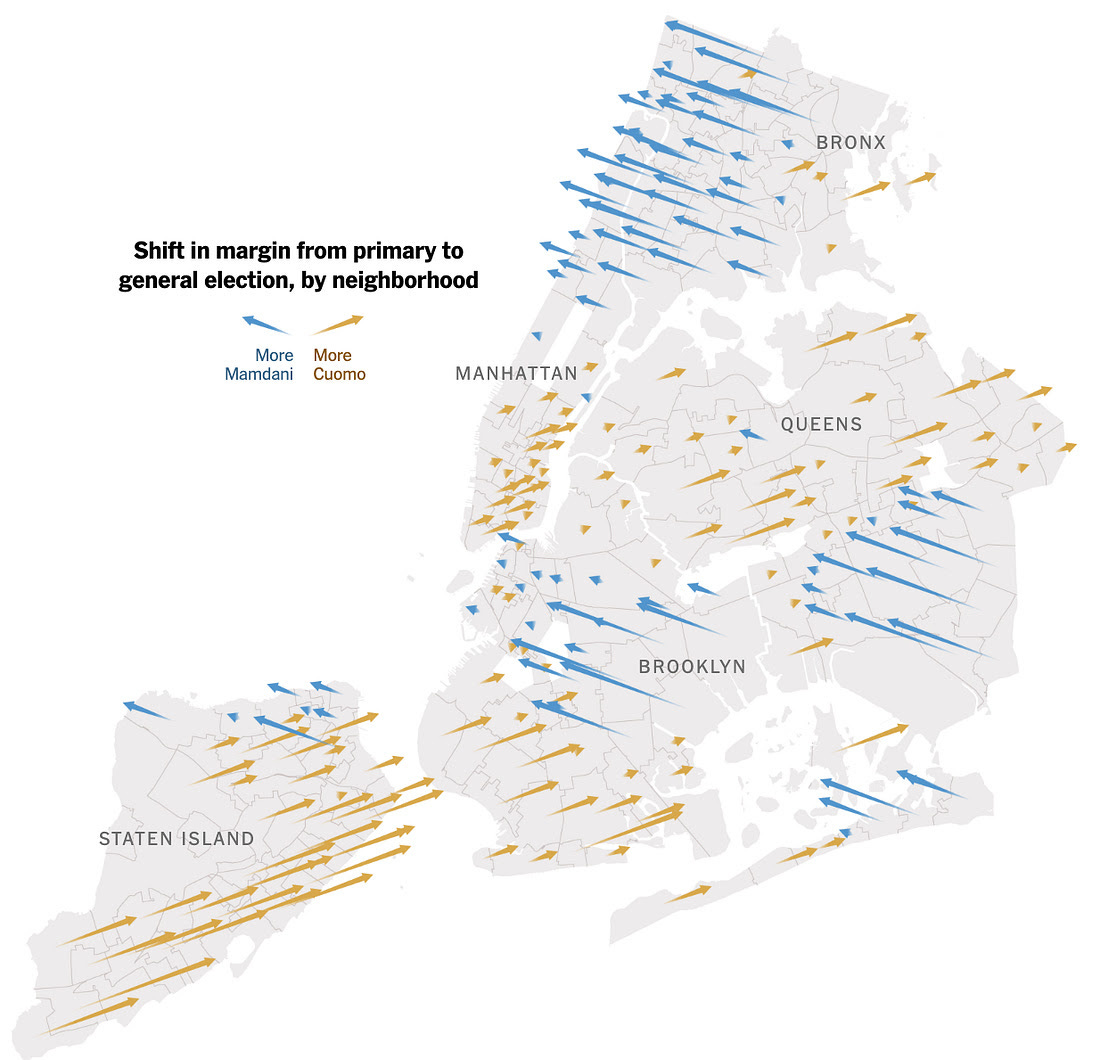

A norm-shattering, era-defining La Guardia-esque realigner Mamdani would not suffer these indignities. But he has to, because he does not have a strong enough coalition to avoid it. The Rainbow coalition of Mamdani’s general election was dramatically weaker than the one he held in the primary. In Astoria and Williamsburg, Commie Corridor neighborhoods that gave Mamdani 85% delivered only 70%. In the outer boroughs, Mamdani maintained his advantage with Muslims and South Asians, but was unable to arrest the sharp rightward slide of East Asians in Bensonhurst and Elmhurst. And as for Manhattan; If Lange can “see the Commie Corridor from space,” then you can see Fifth Avenue from another universe entirely. The anti-Mamdani coalition showed up motivated, and they ran up margins all over the city.

As shown in the map above, Mamdani was able to survive this counterwave only by flipping the Black neighborhoods in outer boroughs. He did this by relentlessly courting their votes, showing up at one Black congregation after another all summer. But he also did this simply by having the capital D next to his name. These are some of the most loyal voters that the Democratic Party has in the whole country. They are not particularly progressive (they supported Cuomo in the primary), they skew older, they are incredibly skeptical of efforts to scale back police, and they are not a natural fit for Mamdani’s renter-focused affordability agenda. Nonetheless, they are now an absolutely indispensable part of his coalition. Mamdani won 50.6% of the vote in the general election. He cannot afford to lose any of it.

With this backdrop, it’s obvious that firing Tisch and appointing a reform-oriented commissioner is not realistic for Mamdani right now. But that’s just one of the many fights that he’s going to have to wage in the near future. Mamdani will want a corporate tax hike to fund his agenda, and Hochul will not want to give it to him. He will want to make some buses free, and he will have to contend not only with a hostile governor but a skeptical, widely popular MTA CEO. He will want to fund some of this with a property tax overhaul, which has support from tenant advocates and landlord lobbyists alike, but is, as commentator Josh Barro put it, “a political minefield.” He is committed to squeezing as much affordable housing as possible from every neighborhood rezoning, but that will engender local opposition at every turn, much of it from within his own coalition. He will need to navigate all of this with a razor-thin margin. It will be very difficult for him to tell any powerful coalition member to screw off.

And he will try to build power across the city: there are at least three spicy congressional primaries to be waged this spring. A La Guardia-esque realigner could use his momentum and significant organizational might to help anoint allies in these roles. So far Mamdani has urged one ally, City Council Member Chi Osse, not to challenge Hakeem Jeffries at all, and has moved to sideline another, DSA State Assembly Member Alexa Aviles, so that the more widely palatable Brad Lander can dislodge Dan Goldman with a clear field. These are not the moves of someone who is ushering in a new era, free from the rules that constrained predecessors. They are the moves of someone who is playing the game, and who recognizes that he is, at the moment, quite constrained.

Lange and Williams both write that Mamdani has inspired New Yorkers to dream, to hope, to expand their ambitions and get excited about city politics for a change, and that this alone is a worthy accomplishment. I agree completely, and this is a tool that he must continue to use as he progresses. Because if he truly wants to take power out of the hands of the “well-connected”, and give it to working people instead, he will have to build a bigger movement than he showed on election night. He will have to do something that no leader has accomplished in my lifetime, not de Blasio, not Adams, not even Obama. He will have to become more popular as he governs.