A Long List of Ex-Lovers (Part I)

Tortured Poets, Taylor Swift's Five Kinds of Songs, and the Dangers of Superficial Autobiography

On Sunday night, Taylor Swift announced her forthcoming eleventh album The Tortured Poets Department, and since then, there’s been one truism held unanimously self-evident by every member of the Swiftiverse, from die-hard “Level 10 Swifties” who live tweet her every Eras Tour stop, Zero Bond visit, and NFL luxury suite appearance, to the casuals like my dad, my coworkers, and my roommate Max, and that is that this will be a breakup album about her ex-boyfriend of six years, British actor Joe Alwyn.

“Joe is quaking right now,” one person texted me moments after Taylor tweeted the album art and tracklist, which promises the song “So Long, London,” on Side B. “Oh man it really is a Joe breakup album,” my sister concurred minutes later.1 According to British tabloids, Mr. Alwyn has similar concerns. “Joe Alwyn is reportedly fearful that Taylor Swift will give away details of their private break-up on her new album,” wrote Ayeesha Walsh of the Mirror. “Taylor Swift's ex Joe Alwyn feels it would be 'SHADY' for popstar to diss him in new album The Tortured Poets Department - but is already concerned about what she could reveal because of 'undeniable' reference to him in title,” reported the Daily Mail Monday morning. The “undeniable reference”, as everyone knows by now, is to a WhatsApp group chat between Alwyn and brooding compatriots Andrew Scott and Paul Mezcal, which Scott dubbed the “Tortured Man Club.”

Of course, in the popular imagination, ex-boyfriends are to Taylor Swift songs what murders are to Agatha Christie novels, bowls of fruit are to Paul Cezanne paintings, and feet are to Quentin Tarantino films: integral, defining subjects that the artist consistently focuses on from one work to the next, even as the peripheral context and details change. In her teenaged heyday, Taylor used to be explicit about the supposedly direct connection between her extremely public private life and her confessional, diaristic songs about love and heartbreak. “There are a couple of people that they’re about, actually,” an eighteen-year-old Taylor told Ellen Degeneres, before openly admitting that she wrote “Forever and Always” about Joe Jonas, and that she was still mad at him for “breaking up with me over the phone in 25 seconds.” (She publicly apologized to Mr. Jonas on Ellen eleven years later during her Lover promotion). “I like writing songs about douchebags who cheat on me,” she sang cheerfully, in her 2009 monologue song for Saturday Night Live. “I like putting their names in the songs so they’re ashamed to go out in public.” This was a reference to the (elite) song “Should’ve Said No,” from her self-titled 2006 debut album, her only released song about infidelity at the time. The name of the song’s cheating antagonist is never mentioned in the lyrics, but the liner notes to the song revealed a not-so-subtle hidden message: “Sam Sam Sam.” For her first five albums, Taylor attached a secret liner note message to every single song on her album, and they often conveyed hints about the song’s celebrity subject.2 On the podcast Switched on Pop, musicologist Nate Sloan classifies three distinct periods of Swiftian dominance: “Nashville Taylor,” (2006-2010, self-titled, Fearless, Speak Now, peppy underdog country teenager with a sequined guitar and an accent), “New York Taylor,” (2012-2015, Red, 1989, forays into pop music, obsessed with fall, various iterations of an aspirational “hipster” aesthetic) and “LA Taylor,” (2017-2019, reputation, Lover, cryptic tweets, minimal public presence, innovative stadium pop sounds).3 The meta-textual celebrity ex-boyfriend narrative was a key part of the marketing and overall appeal of “Nashville Taylor,” and was one of the main ways fans of that period were taught to consume her output as both an artist and as a celebrity.

This strategy worked incredibly well for a time, but it eventually became personally annoying to Taylor, who by 1989 had begun to think of herself (correctly) as a serious artist worthy of nuanced, intellectual consideration, and was immensely frustrated that interviewers kept asking her about her dating life instead of her art. It also became grating to the general public, because as fun and exciting as the celebrity gossip may have been, everyone could feel after a while that it was fundamentally inauthentic. The songs were too epic, too overwrought, too specific and viscerally searing to refer to six-week “relationships” that clearly involved the couple’s respective publicists spending more time together than the actual couple. And some of them dealt with adult themes like marriage, divorce, death, and generational trauma, topics that a privileged Pennsylvania teenager clearly had no personal experience with. Rather than recognizing this as a sign that Taylor’s talent had outgrown the constricting box of “buzzy celebrity teen girl” that she had previously fit into so successfully, the public decided that she was “fake,” that she was “calculated,” and that she always “played the victim.”

Listening back to Speak Now, my personal favorite Taylor Swift album, I find it so depressing that listeners in 2010 (myself included) were burdened with all of the meta-textual narrative, because it distracts from how amazing the songs are on their own. I can listen to “Back to December,” and enjoy how richly she captures the regret and nostalgia of a recent breakup (and how effectively her producer uses cellos in the pre-chorus), without having to think about a specific werewolf actor who everyone in my sixth grade class has a crush on. I can enjoy “Enchanted” for its startlingly accurate depiction of internally developing a tiny crush into a full-fledged bonfire despite having no basis for the crush whatsoever, without having to speculate about whether the dude from Owl City is going to text her back. This is not revisionist history on my part, because the songs were never really about those guys in the first place. Authorial intent is impossible to definitively establish (and fundamentally irrelevant anyway, because the songs belong to their audience), but in this case I am on solid ground. In her 2019 Tiny Desk, Taylor described her approach to writing break-up songs as a teenager:

“I started out writing songs about stuff I had no idea about. Like I started writing songs when I was nine years old and they were usually about heartbreak and I had no idea what I was talking about, but I had watched movies and I had read books, so I would grab inspiration from character dynamics… [later on] I would watch a bunch of movies about break-ups, and listen to my friends who were going through break-ups, and then one day I would wake up and have all these break-up lyrics in my head.”

Taylor is echoing Bruce Springsteen here, who told his Broadway audience that despite writing hundreds of songs about blue collar workers, “I’ve never held an honest job in my life! I’ve never done any hard labor. I’ve never worked 9-to-5. I made it all up!” She’s also following in the line of hundreds of fiction writers who repeatedly insist that their work is not purely autobiographical, not just because they believe that it is not, but because their work would be so much more boring and constricted if it was. Art is supposed to mean different things to different people, it’s supposed to be ambiguous, it’s supposed to tell a made up story in a way that people can connect to even if they haven’t experienced that exact thing. Celebrity buzz may provide more of a sugar high, but it can’t compete with that.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is my contention that Taylor Swift has written almost no autobiographical songs. Here are the different kinds of Taylor Swift songs, categorized by authorial distance from the subject:

Directly Autobiographical Songs: There are at least 214 Taylor Swift songs and I posit that there are exactly three that are directly autobiographical: “Soon, You’ll Get Better,” about her mom’s battle with breast cancer, “marjorie,” about her late grandmother, and “the last great american dynasty,” mostly about the oil heiress Rebekah Harkness and her house in Watch Hill, Rhode Island, but which does reference her 2013 purchase of that house in the bridge. That’s it. These songs include a specific narrator who uses the “I” perspective, who have distinctive attributes or details that precisely match Taylor Swift, and crucially, do not match most other people (most people do not have mothers with breast cancer, grandmothers named Marjorie, or houses called “Holiday House” in Watch Hill, Rhode Island). And Taylor has publicly, repeatedly highlighted these attributes and explicitly connected them to herself (she says “this song is about my grandmother Marjorie” verbatim in each Eras Tour show.) Almost none of her other songs meet the former criteria4, and absolutely none meet both.

Third Person Songs (Obviously Not Autobiographical): These songs feature third person characters as their protagonists, and those characters are named something other than “Taylor.” These songs were quite rare until folklore and evermore, which are both chock full of them, including “betty,” “cardigan,” “august,” “dorothea,” “tis the damn season,” and “no body no crime.”5

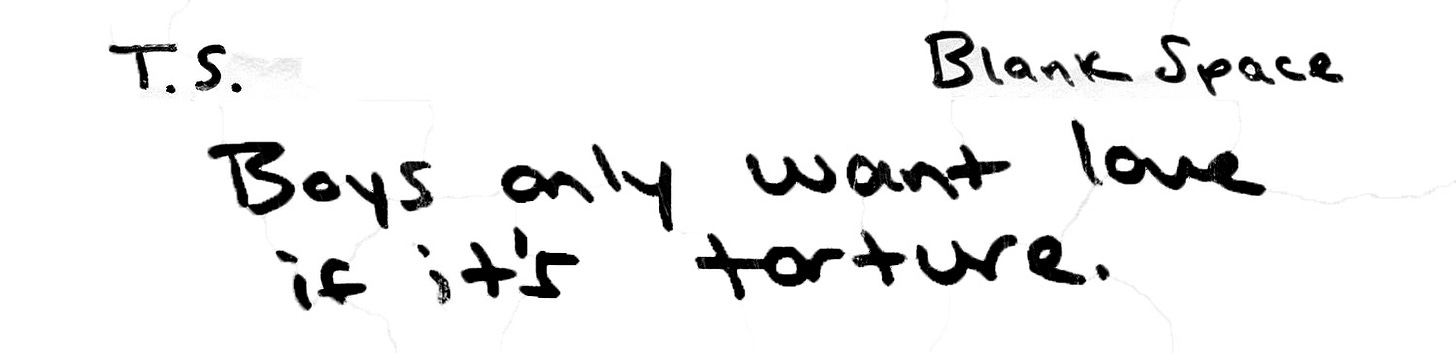

Self Parody (Not Autobiographical): “In the last couple of years the media have had a wonderful fixation on painting me as a psycho serial dater girl,” Taylor told the audience at the Grammy Museum in LA, before an acoustic performance of “Blank Space.” “Every single article had a description of a personality that was very different from my actual personality… my first reaction was that it was a bummer, but my second reaction was ‘that’s actually an interesting character they’re writing about.’ And I thought ‘I can use this!’” “Blank Space,” is told from the perspective of a mythical Taylor Swift who embodies all of the man-eating characteristics of her (fictional) celebrity reputation. This capacity for self-aware, meta commentary and parody is one of the key innovations that distinguishes “LA Taylor” from “New York Taylor.” It characterizes not only “Blank Space” but also “mad woman,” “Vigilante Shit,” “Anti-Hero,” and of course, nearly every single song on “reputation,” an album in which Taylor embodies the public perception of that time that she was not only a man-eater but a duplicitous supervillain. These songs are in many ways the opposite of autobiographical, they are told from the perspective of a fictional character whose defining characteristic is being not Taylor Swift.

First Person, but Clearly Fantastical/Fictional:

Taylor Swift has never robbed a bank. She has never been either the archer or the prey. She has never interrupted a wedding to declare her love for the groom. She has never dated anyone who worked part-time waiting tables, nor is she a careless man’s careful daughter (her dad was a Vice President at Merryl Lynch!) She wears plenty of short skirts.

First Person, Ambiguous: Most of her songs, especially on her first four albums, are straightforward, diaristic expressions of a person with an intense emotion. A lot of these people are in love. And hey, nineteen-year-old Taylor was also a person who had intense emotion and had maybe been in love, but so was everyone else! Maybe her experience going on three dates with John Mayer in 2008 motivated her to write about being treated badly by an older boyfriend. Maybe she just wanted an excuse to write a bridge with his style of electric guitar solo. Either way, a song is not autobiographical if it is inspired by a specific relationship. Everything is inspired by everything! It is autobiographical if it is about that relationship.

This is all subjective, and at the end of the day, I have no more authority to declare what a song is about than anyone else. All I can tell you is that the songs are, in my opinion, much richer, more compelling, and much more important if you free them from the particular circumstances of the marketing strategies surrounding their releases more than ten years ago.

Taylor seems to agree with me on this front, which is why it’s great that she took the opportunity at her show in Minneapolis last June to formally disconnect “Dear John” from John Mayer, and reveal that it had actually had nothing to do with him…

Damn it. In part two of this essay next week, I’ll explain why Taylor seems to still enjoy using the allure of celebrity autobiography to market her songs a decade after it backfired so horribly for her.

People outside my immediate social circles think this too. Cosmopolitan magazine has helpfully aggregated an assortment of fan tweets on the subject.

The most wildly overt messages are “Tay” (for Taylor Lautner, on “Back to December), “Ashley Dianna Claire Selena,” (“22,” during the onset of her “girl squad” years), and weirdest of all, “Hyannis Port,” (“Everything Has Changed,” apparently about the one summer where she anachronistically dated a Kennedy scion).

Since then, at least two new periods have ensued, which Sloan has not classified, but which I will call “Log Cabin Taylor” (2020-2021, folklore, evermore, incredible art, goofy appearances on zoom late night talk shows), and “Teterboro Taylor” (2023-present, Midnights, Eras Tour)

Cornelia Street comes the closest. She did actually rent a place on Cornelia Street in 2016, and it’s a very small and expensive street. Others like “invisible string,” which references visiting Centennial Park in Nashville, a large public park in a big city, are less convincing. And we’ll get to it in a bit but having a boyfriend named Drew or John does not count as an identifiable trait. These are (intentionally) very very common names.

“When Emma Falls In Love,” from the vault of Speak Now, is an interesting case because it is mostly about a third person protagonist, but then does mention the singer’s personal feelings about this protagonist. This was enough to lead the public to speculate that it was about Emma Stone, who has hung out with Taylor a few times but from everything I know about her is absolutely nothing like how I would imagine Cleopatra, Queen of Ancient Egypt, if she grew up in a small town.

Extra fun sports-free column today