Managing the Ghosts

Six Flawed Models for What the Heck a Head Coach Actually Does.

The 2023 MLB season wrapped up last Sunday, which meant that this was the week to fire your manager. So far, the Mets’ Buck Showalter, the Guardians’ Terry Francona, the Giants’ Gabe Kapler, and the Angels’ Phil Nevin have all announced their departures. All breakups are different; some managers claimed that the decision was mutual, others made it clear that they had gotten dumped. Francona announced that he was retiring from managing to focus on his health (“it’s not you, it’s me”).

Why fire a head coach? Probably because he wasn’t doing his job well enough, and because you think someone else could do it better. But what exactly is the job of a head coach of a professional sports team anyway? Well, there are a few models.

I.

Model 1: Inspirational leader of men. This is the most common kind of coaching in popular culture, from Ted Lasso, to Coach Taylor in Friday Night Lights, to Herb Brooks in Miracle on Ice. Give everyone in the locker room a special personalized inspirational quote that compels them to greatness. Hold people accountable, bench the cocky, arrogant superstar for the unselfish, hardworking backup. Make everyone run sprints until they puke. Most importantly, before each game, deliver a stirring speech about the triumph of the human spirit. Clear eyes, full hearts etc.

Reality check: This all makes sense in the context of high school and maybe college, but shouldn’t 30-year old professional athletes be pretty immune to this stuff? They’ve been playing since they were nine, they’ve heard thousands of speeches, and they’ve surely figured out whatever they need to do to motivate themselves without your help. As for being a hardass disciplinarian, well, anyone can scream at high schoolers. But try telling Giancarlo Stanton to “get your head out of your ass” or “drop and give me five pushups for each strikeout you had last week.” He’s 6’6, 245 pounds, he makes $32 million a year, and he has more than a million followers on Instagram. If you piss him off, it’s not gonna go well and no one is taking your side.

Model 2: Tactical mastermind. The manager gets to make a lot of decisions that directly impact the game, so make sure all of these decisions are correct. The lineups should be perfectly constructed. Your situational strategy should be flawless; this person should bunt in this scenario, this person should steal. The starting pitcher should be removed at the exact right moment, and replaced with the optimal sequence of relievers. Pinch hitters, pinch runners, and other substitutions matter too, but it’s the bullpen that is really going to be where you prove your value if you are this kind of manager, because that’s the most emotionally volatile area for the fans. When you’re up two in the fifth inning of a close play-off game and your beloved veteran ace has just walked two straight and now the go-ahead runner is at the plate, it’s your responsibility to fix that. Do you trust your guy to “battle” and “work through it” and “grind it out”? According to some fans, this is the only honorable option. Back in their day, pitchers were expected to finish their games, why has everyone gotten so soft? Or do you follow the lead of the modern analytics wisdom that pitchers decline precipitously on their third time through the order, and call in a reliever? If so, which reliever? Your best one? It’s only the sixth inning, what if you need him later on? What if the batters coming up are lefties, but your best lefty reliever threw 20 pitches yesterday? The permutations are endless, but the point is that the vibes are tense, the spotlight is on you (the TV broadcast is surely cutting to you after practically every single pitch), and no matter how sound your logic may be, if those runs score it will be squarely your fault. Watching your team blow a lead in the later innings of an important game is one of the most painful experiences a fan suffers through, and it’s your job to guard them from this cruel fate.

Reality Check: This is undoubtedly an important part of the job of an MLB manager. But on its own, it’s inadequate as an explanation for why fans feel the way they do about their manager. For one thing, these decisions are impossible to evaluate objectively, because however badly things go, you can never know what would have happened had the manager made a different decision. The manager can always plausibly claim that their reasoning for their decision was sound, and that the alternative would likely have been even worse. Secondly, most of the time these decisions don’t matter all that much. At the end of the day, baseball outcomes are pretty random and have a lot of variance, and in any specific at-bat, the difference between a good pitcher and a bad one is at most tenths of a run in expectation. But thirdly, successful, admired managers frequently do make disastrous bullpen decisions without reputational consequences. Cubs manager Joe Maddon’s flagrant overuse of Aroldis Chapman in the 2016 World Series (which led to Chapman surrendering a game-tying home run in Game 7) did not prevent the Angels from offering Maddon one of the most expensive managing contracts in league history in 2020. In that same postseason, Orioles manager Buck Showalter’s refusal to use historically dominant closer Zach Britton was widely decried as a series-losing blunder. Seven years later, Buck is still beloved and respected, and is completing a two-year stint managing the Mets. He has not improved much in the way of bullpen management, but Mets fans are grieving his departure, even after one of the most disastrous seasons in recent memory (even by Mets standards). Ultimately, in-game tactics are part of the role, but they are not the sole, or even the main, determinant of success.1

Model 3: Skill Developer. Your pitchers should show up and immediately increase their spin rate. Replacement level hitters should change their swing and start mashing 400-foot homers. Every year a new unheralded rookie should emerge as an All Star. This is the area where the Rays and Astros shine. The equivalent in the NBA is the Miami Heat, who seem to manufacture 40% three-point shooters who play gritty defense from thin air, (or from Western Massachusetts’s finest DIII small liberal arts institution). If you can teach your bad players to be good instead of being bad, this is obviously a massive competitive advantage for your team.

Reality Check: I don’t know about the NBA, but in baseball, the position coaches are the ones who are in charge of skill development, not the manager. And even then, the pitching coach is at most giving tips on small adjustments to make (“throw more sliders”), while the hitting coach is looking for similar adjustments (“stop swinging at so many sliders.”) The real skill development happens in the offseason, with private, personal coaches, in homemade warehouses, far away from the team staff, so even if the head coach decided to micromanage his position coaches and personally oversee every drill, there’s only so much he can do. But you probably won’t micromanage too much, because you’re too busy being the…

Model 4: Spokesperson. The public face of the team. After every game say something irascible and grumpy about how “we need to do better.” But also “stand up for your guys” when a reporter asks about why one of your players sucks. There are different styles of this, from heartfelt, emotional speeches about how much you love and appreciate the guys for how hard they fight (Dan Campbell, Joe Girardi, Steve Kerr) to wise, weathered philosopher genius expounding on the fundamental truths of the sport (Pete Carroll, Greg Popovich), to fascist sociopath with nothing but contempt and disgust for the idiot reporters who have the nerve to ask him questions (Belichick, Coach K, Saban, Jose Mourinho, Urban Meyer, there are a lot of these).

Reality Check: The moments I’ve highlighted are outliers. Ninety-nine percent of the time, the coaches are out there repeating the same exact meaningless platitudes about how “we need to do better” and “clean things up” but also how “I’m happy with how hard my guy fought,” without any meaningful variation. I’ve listened to every single Aaron Boone-Jomboy interview this year, and most of the time he just finds elegant ways to say absolutely nothing, like any good press secretary. And of course, this is very frustrating for angry, emotional fans who want to see some of that emotion mirrored in their leader! That’s why you also have to be a…

Model 5: Rage Outlet. It’s important to get angry at the officials on camera every once in a while, to fire up your team, draw attention away from an angry player at risk of getting himself ejected, or just to let the fans know that their feelings are valid and that you care as much as they do. In baseball, the best way to do this is to get yourself ejected intentionally. Go out there, scream at the ump, kick some dirt, then storm off the field, hand the lineup card to your bench coach2, and watch the rest of the game from the clubhouse on TV. Baseball managers perform this ritual at least once a month. Often their rage is authentic, but other times they don’t care, and explicitly ask the umpires to eject them anyway. “I know that was the right call, but we stink so you are gonna have to run me,” Terry Collins once yelled at umpire Dale Stott. These days, umpires understand the mechanics of this ritual, and will ask managers whether they want to be ejected. This makes for excellent content, especially when there are miscommunications. Last year, Umpire Bill Welke asked Red Sox manager Alex Cora if he “wanted to get run” after discussing a replay review ruling. Cora didn’t actually care about the ruling (a relatively-low stakes call in a game the Red Sox were already losing by a lot), so he replied “No, I don’t wanna get run for this shit,” but Welke misunderstood and ejected him. “I said I DIDNT want to get run! Why would I want to get run for this?” a now genuinely irate Cora spluttered repeatedly.

Managers get themselves intentionally ejected quite frequently (despite incurring fines from the league each time they do), the team is always fine without them, and as any bored undergrad intern will tell you, if your coworkers don’t care if you leave frequently halfway through the workday, they might not actually need you very much.

II.

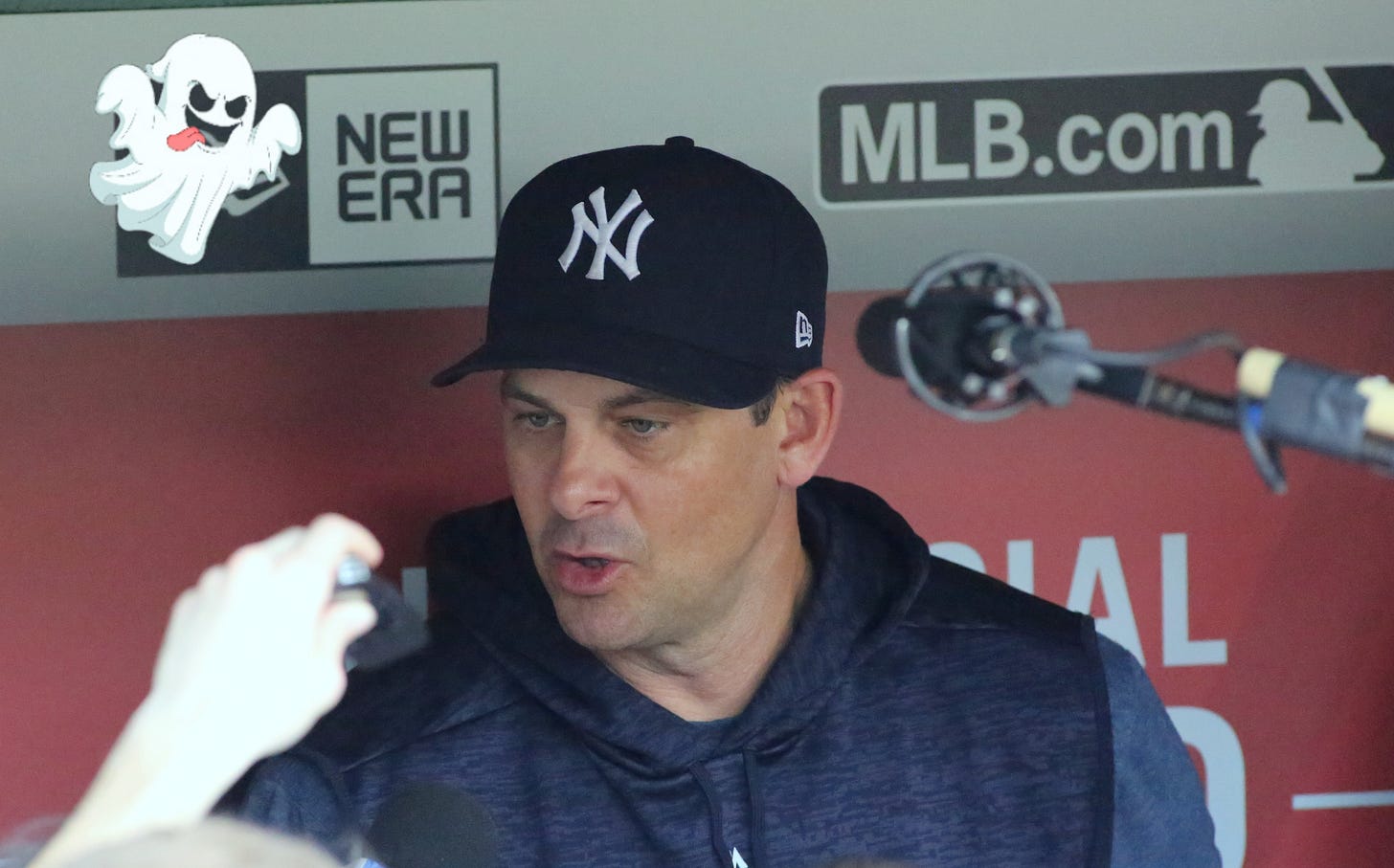

All indications point to Aaron Boone keeping his job for at least another year, and many Yankees fans are furious. After all, the Yankees have catastrophically underperformed in two of the past three seasons, despite having one of the most expensive rosters in the league. Surely a better manager would be able to do more with all that talent, the thinking goes. But if you accept my model of a manager’s responsibilities, it’s hard to find a specific area where Boone falls short. Is he an inspirational leader of men, who holds his players accountable and fills their hearts with hope and adrenaline? Hard to say, we don’t get access to his pre-game speeches, but his players seem to like playing for him a lot. Is he a tactical mastermind? Some fans would say no, I think he does a decent job. At the very least, in his six seasons as a manager he has yet to make a single truly egregious playoff blunder like Kevin Cash and Buck Showalter. The Boone era has seen the improbable skill development of All-Stars Jose Trevino, Clay Holmes, Matt Carpenter, and Nestor Cortes Jr, not to mention the continued growth of Aaron Judge into one of the best hitters of all time. Plenty of other players have stagnated, or gotten worse, and as I said, I’m skeptical of how much Boone is really involved in any of this, but it’s hard to say he’s doing a bad job here. As for public performance, I’ve always enjoyed his press conferences, and when it comes to manager ejections, there’s simply no one better.3

Where Boone falls short, unfortunately, is in Model #6, which at the end of the day, is the only one that matters to fans.

Model #6: Ghostbuster. Come in and change the vibes. Show us something new! Give us a tangible explanation for how this year will be different than last year, that you can escape the horrors of your history. For the Yankees, this wasn’t always so hard, because for a while, our history was awesome. Under this model, Joe Torre was the best manager not because of any of the stuff he did actually managing the team, but because when we looked at him, we remembered him holding a trophy, and it reminded us that we were rooting for a team that had won four championships in five years. There was continuity, this was the same team as that one, so there was hope.

By the end of the aughts, that hope had curdled into dread, as the memory of nineties glory was drowned out by Mariano Rivera’s blown save in Game 7 of the 2001 World Series, the Red Sox comeback from down 3 games in the 2004 ALCS, and the midges attacking Joba Chamberlain in 2007.

Girardi was a fresh face, who had played for the Yankees from 1996 to 1999, during the height of their hegemonic rule. He represented a fresh team that was fundamentally different from the ones that had suffered through all those aughts traumas (with virtually the exact same roster), yet still had connection to the nineties champions (although most of those players, like Girardi, had long since retired). He was there to vanquish the bad ghosts, but keep the good ones around. I know this sounds ridiculous, but you can’t argue with the results. The Yankees won the World Series in 2009, in the second year of Girardi’s tenure.

Boone has a similar origin story. As a player, he hit the walk-off home run against the Red Sox to send the Yankees to the 2003 World Series, the last time that the Yankees would ever feel truly dominant in that rivalry. He departed before the start of the next year, avoiding the 2004 catastrophe entirely, so he was also a token of good Yankees ghosts without the bad ones. And it seemed to work for a while: the Yankees made the playoffs for all of his first five seasons, made the ALCS in 2019 and 2022, and have consistently been one of the best teams in the league.

But as I’ve written here before, the ghosts have started to accumulate, and it’s getting harder for Boone to claim that he is the right person to vanquish them. The team will give him one more year, because he’s a good leader, makes smart tactical decisions, gets his players to develop well, says the right things to the media, and is a generationally elite umpire antagonist. But unless next year goes astonishingly well, none of that will matter. We will need a new face to bust ghosts, one with a brief, entirely positive history with the Yankees. Like Nick Swisher. Or CC Sabathia. Or maybe even Jerry Hairston Jr!

Still though, it’s interesting that there are some head coaches of professional sports teams that are obviously, demonstrably bad at this part of the job. This comes up a lot especially in football. I just watched Ron Rivera’s Commanders kick a field goal down 16 on 4th and 2 in the third quarter. This is obviously a situation where it is better to go for it, this win-probability calculator said the mistake cost the Commanders nearly 4 expected points, the live betting markets agreed and moved away from the Commanders even after the field goal was good, which means they scored 3 points and their odds of winning got worse! That’s not supposed to happen! And it’s just weird that all of this was obvious to me and everyone else watching the game, but not to Rivera, who has coached professional football for 26 years.

Don’t even get me started on the models of bench coaches. I have truly no idea what they do. Do they coach the benched players, the backups who didn’t start that day (who therefore probably don’t need much coaching)? Do they coach the players who happen to be sitting on the bench? Make sure vibes are good, police bad language, encourage the proper disposal of gum and sunflower seeds that the players love to spew onto the floor? Or do they… coach the bench? Is there security footage somewhere of Phil Nevin whispering Sun Tzu quotes to a piece of furniture? Are there some benches that are left on the street because they were deemed “uncoachable?”

He loves to give the umpire constructive feedback even in his angriest moments. “You can make the adjustment! It’s not too late! There’s still time!” he’ll scream at the top of his lungs. “You’re off to a really bad start… I feel bad for you, but get better, man. Let’s tighten this shit up!” It’s hilarious obviously, but it also seems like a really good quality for a coach!!