On Momentum (Part I)

A Guide to the 2024 Yankees Haunted Starting Rotation

This is part one of what will be a series on the five pitchers in the Yankees starting rotation, their metaphysical history, and the ghosts that they must exorcise. It is also a spiritual sequel to my Great Volpening series, which explored the team’s spooky history and trauma with the shortstop position in advance of 2023 Opening Day, and (not to brag) correctly foreshadowed Volpe’s disappointing rookie season. This year’s gonna be different though…

“Momentum? Momentum is the next day’s starting pitcher,” legendary Orioles manager Earl Weaver once said about the difficulty of sustaining a winning (or losing) streak in the MLB. On some level, this is incredibly reassuring for Yankees fans, whose momentum would be dragging them down into the depths of mediocrity and pain if it could easily transfer from last season to this one. By their standards, the Yankees were awful last year, with an 82-80 record (their worst in 30 years), the 5th-worst offense in the league, and a teamwide batting average of .227 (29th of 30). Their 2024 campaign depends entirely on the premise that momentum does not exist in baseball, that last year was a bizarre anomaly, and that things will be different.

But Weaver’s wisdom also raises concrete anxieties for Yankees fans. For the first time in my lifetime, the Yankees open the season with no ace, as reigning Cy Young winner Gerrit Cole recovers (we hope) from an ambiguous arm ailment that will sideline him for at least two months. The five brave men that will step up in his wake, the starting pitchers that will protect us from downward momentum, and maybe even build some momentum in the opposite direction, are all rich, psychological characters riddled with issues, eccentricities, and yes, ghosts. At the moment, they represent the biggest weak spot in an otherwise formidable 2024 squad. They also represent the team’s greatest hope, because if they can all escape the things that haunt them and ascend to their true forms, they have the potential to collectively be the best pitching staff in the league. So it’s important that we take a hard look at all of these ghosts, and understand how we got here.

In the later years of World War I, French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau is said to have been dissatisfied with the state of the battlefield.1 The tactics that had worked so well in the past century of warfare, like outflanking the opposing army in the open field, leading heroic charges with cavalry on horseback,2 and marrying into Austrian aristocracy, could no longer stand up to modern innovations like machine guns, trenches, and poison gas. “Generals always prepare to fight the last war,” he complained to his staff, probably in French.

I’ve been writing this blog for a year, and while I’ve covered a few different topics (the Yankees, Taylor Swift, Sam Bankman Fried, the Knicks, Taylor Swift again), I’ve focused on the idea that the past matters, that ghosts are everywhere, that institutions have collective memories and traumas, and that they can lie dormant for years before rearing their heads and wreaking havoc. “The past isn’t dead,” I quoted from William Faulker’s Requiem for a Nun in my first Volpening blog, “It isn’t even past.” Generals fighting the last war is perhaps the most obvious mechanism by which an institution’s past can remain alive. The generals’ fear of repeating the specific horrors of the past, and their hard-won expertise in how to combat those specific horrors, cloud their judgment and cause them to overcompensate in the present, overlooking new developments that inevitably lead to new horrors, and the cycle repeats.

In the case of this Yankee season, the generals3 have made it clear that they will do anything to keep the lineup from hitting as poorly as it did last year. Specifically, they will do anything to make sure that the lineup has more lefties, has three competent hitters in the outfield, and has more people that can get on base rather than just swinging for the fences. In the past few seasons, the Yankees have brought in many, many left-handed outfielders4 and none have been able to provide these things. The generals wanted to solve this once and for all, so on December 5th, the Yankees traded three prospects to the Red Sox for outfielder Alex Verdugo. Verdugo became a clubhouse nuisance in Boston last year, and the Yankees usually don’t like to send prospects to their fiercest rivals, but Verdugo is a decent left-handed hitter with an above average career on-base percentage, so they were willing to overlook anything.

This alone would have reeked of extreme desperation, but the next day the generals doubled down. When the San Diego Padres declared that they had no interest in signing generational talent left-handed outfielder Juan Soto to a long-term deal, and sought to recoup some value for the last year of team-control5, the Yankees lunged in, and by the end of the day, the two teams had reached a deal. The Padres would receive touted pitching prospect Drew Thorpe, long-tenured fan-favorite catcher Kyle Higashioka6, and three MLB-caliber pitchers, Michael King, Randy Vazquez, and Johnny Brito. The Yankees would receive Soto, and yet another left-handed outfielder, the veteran Trent Grisham.

If the left-handed Verdugo is an above-average on-base hitter, the left-handed Soto is, at age 25, by far the best on-base hitter in the league, and one of the very best of all-time. He has a career on-base percentage of .421 (to Verdugo’s .337), and has led the league in walks for the past three seasons. But they are similar archetypes, and by acquiring Verdugo, Soto, and Grisham in the span of 48 hours, it was as if the Yankees had gotten sick of walking to work every day, bought a used Audi, then read the carfax report and some negative reviews online, and in a panic had gone out the next day and bought a new Maserati, and also a Prius, just to be safe.

I’m psyched about the Maserati. The next day, Michael Baumann of Fangraphs.com published an article with the headline “Juan Soto is Going to Score a Bajillion Runs in Front of Aaron Judge,” and if you want to feel like you can run through a brick wall, I encourage you to read it. But the team only has so much garage space. They can only play three outfielders at a time, and they already have Aaron Judge. Also, Maseratis are expensive. King, Vasquez, and Brito left holes in the team’s pitching staff. With Drew Thorpe gone, the Yankees no longer had the tradable assets to fill those holes, so they were unable to make a competitive offer when, for example, 2021 Cy Young Award Winner Corbin Burnes became available (the Orioles got him instead). And with Soto’s $30 million salary (the largest ever awarded to a player under “team-control,” but still a heavy discount compared to what he is projected to get in free agency next year) on their books, they no longer had the appetite to sign an elite pitcher in free agency, opting to pass on dominant free agent aces Jordan Montgomery and Blake Snell.

By acquiring Soto (and Verdugo and Grisham), and deploying all of their offseason resources towards bolstering the lineup, the Yankees have neglected the pitching staff, even weakened it slightly. This was a calculated risk, and based on the Last War, it was one the generals felt good about. After all, pitching wasn’t the problem last year. In 2023, the Yankees had a decent rotation of starters, the best bullpen in the league, and Cy Young Award winner Gerrit Cole, the best pitcher of his generation having the best season of his career, whose consistent, singular dominance provided the team with a small bright spot in an otherwise miserable year. When the Yankees were at their worst last year, Cole embodied the Weaver quote, briefly stopping their downward momentum and dragging the team to victory in 23 of his 31 starts. As long as we had Cole, the generals reasoned, the pitching staff would be fine.

Well, Cole is out, and while he seems to have escaped a diagnosis that would lead to season-ending surgery for now, his projected June return is written in highly erasable pencil. If he returns, there is no guarantee that he will be his usual dominant self. Most pitchers with mysterious arm inflammation issues usually aren’t.

Instead, the Yankees will place their momentum into the hands of a quintet of flawed, intriguing, deeply haunted oddballs. The generals must now hope that they can rise to the occasion and vanquish their ghosts, so that they are not punished for once again fighting the last war. Here are their stories:

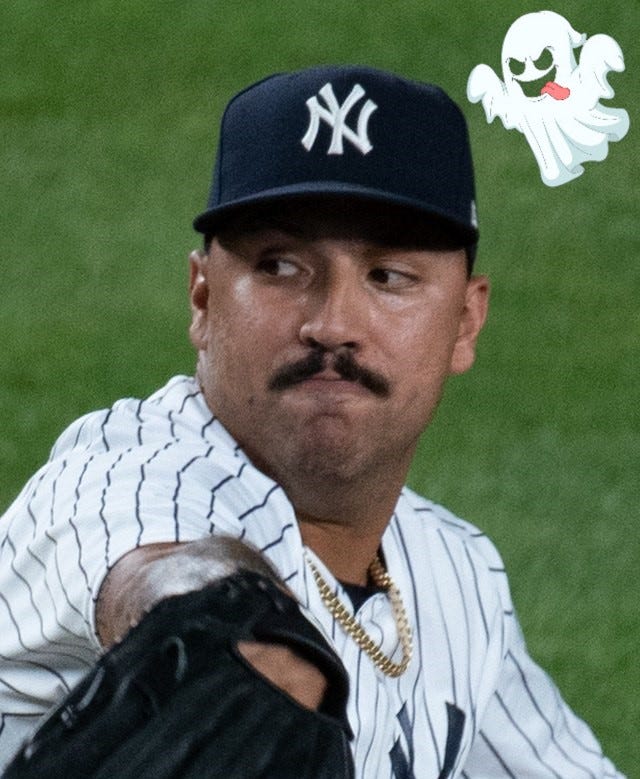

Nestor Cortes Jr:

Profile: Age 29, 5-11, 210 lb, LHP

Contract: one-year, $3.95 million (arbitration year two), free agent in 2026.

Best Season: 2022, 158 IP, 163 SO, 2.44 ERA (161 ERA+), 4.4 WAR, AS, CY-8

2024 ZIPS Projection: 102 IP, 99 SO, 3.86 ERA, 2.0 WAR

On July 24th, 2019, the Yankees eked out an ugly 10-7 victory on the road against the division-leading Minnesota Twins. It was ugly mostly because JA Happ, former Toronto Blue Jays ace and then-current Yankees disappointment, got lit up again, surrendering six runs in three-and-a-third innings. Happily the Yankees had scored nine in the same number of innings (the 2019 Yankees offense was really something else), but Boone couldn’t let Happ squander yet another big lead. With most of the bullpen depleted from an extra-innings win the night before (a 14-12 offensive monstrosity punctuated by a game-saving Aaron Hicks layout catch), Boone turned to 25-year old rookie Nestor Cortes Jr., considered at the time to be the very worst pitcher in the bullpen.

Nestor threw a tortoise-like fastball that barely grazed 90mph, an unconvincing slider, and a change-up that was not that much slower than the fastball, because how could it be. He was also 5-11, with a wispy mustache and a more fleshy, rotund body than Major League Baseball hitters are accustomed to facing down. But improbably, against one of the most explosive lineups in the league, Nestor delivered, surrendering only one run in three innings before handing the ball to more-established bullpen arms Tommy Kahnle and Aroldis Chapman. Fans found this to be an incredibly endearing and heroic performance. “Post this jester 🤡 to say thank you Nestor,” someone wrote in the Yankees sub-reddit game thread, and everyone complied, filling the screen with clown emojis.

Nestor didn’t do much else that season, and was eventually sent back down to the minors, then bounced to the minor league teams of the Mariners and then Orioles. That was okay. He had made us proud that one night in July. Two years later, when the Yankees faced another midseason bullpen crunch, fans were delighted to see him return, if only so that we could post more clown emojis. But this time, Nestor quickly established himself as more than a clown, transitioning from a bullpen role to the back end of the starting rotation, and then putting together a string of decent starts. He couldn’t go deep into games, but he could consistently pitch exactly five innings, give up two or three runs, and give the team a decent shot to win. This is a dream outcome for another team’s discarded minor-league pitcher, the most value you can reasonably expect out of a bargain bin bonanza in a league where quality starting pitchers are so scarce and valuable. Nestor was penciled in as the fifth starter for 2022, and fans hoped that he would defy the odds and continue to be decent.

No one in their wildest dreams could have dared to ask for what came next. Still building up to full-strength due to the lockout-shortened spring training, Nestor came out of the gate in the spring of 2022 with a four-inning shutout against the Blue Jays. He followed it up with a five-inning shutout against the Orioles, which was not that impressive, given that the Orioles were awful, except that in those five innings he got twelve strikeouts. He finally gave up his first run of the year in his next start, on a home-run to Josh Naylor. That was the only hit he gave up that game, and he struck out eight. This kept happening. Nestor’s fastball had not gained any velocity, his slider hadn’t doubled its spin rate, and he certainly hadn’t gotten into better shape. But his mustache was no longer quite so wispy, and more to the point, he was pitching better than not just current teammates Gerrit Cole and Jordan Montgomery, but basically any other Yankee pitcher in my lifetime. Through ten starts, Nestor had pitched 60 innings, struck out 68 batters, and allowed only 10 earned runs, a 1.50 ERA. He was no longer “Nestor the Jester,” an amusing, endearing clown on the periphery of the bullpen. He had become “Nasty Nestor,” a genuine stud who struck terror into the hearts of the elite hitters that he routinely humiliated. He had also become, statistically, the best pitcher in the league.

Nestor couldn’t sustain this level of excellence for the back half of the 2022 season, but he remained a consistent, winning pitcher. Crucially, he also remained fun. He proved to be deceptively athletic, frequently making epic lunges to tag out runners during tricky infield grounders. “Under this body, there is an athlete,” he told reporters after making one such play. When he fielded a comebacker, hit so scorchingly that it knocked him over on the mound, during Game 2 of the ALDS, with the bases loaded and two outs, thousands of fans and I chanted “Under this body, there is an athlete,” together, over and over, as an expression of gratitude to his nastiness.

And he made up for his lack of velocity and spin rate with clever tricks, constantly altering his release point, timing, and even his windup, to confuse hitters. These tricks are usually associated with worse, more desperate pitchers, but well into his nastiness era, Nestor would from time to time lift his right leg up into a windup, and then just hold it there, balancing on his left foot indefinitely, wiggling around, sometimes even spinning 180 degrees to look at the runner on second, before wiggling back and then somehow regaining enough body momentum to launch a (not that fast) fastball at the plate. The batter would blink perplexedly, the umpire would call strike three, and the crowd would go absolutely nuts.

Last year, Nestor was not so nasty. The physiological explanation was that after a decent beginning, he strained his rotator cuff, tried to pitch through it for a month with poor results, and then sat out most of the year. This happens. Hopefully he won’t do it again. Not a big deal.

The metaphysical explanation is that no one man can sustain this level of nastiness for long, that a pitcher of Nestor’s caliber is inevitably due for a regression to his prior career average, that tricks can only fool hitters for so long, that lightning never strikes twice, that nothing gold can stay. Most aspects of professional baseball are concrete, and come from sweaty, incremental improvements, tiny upticks in spin rate or bat speed hard-won over hundreds of hours of repetitive drilling and finely-honed mechanics in a lab with MIT-trained specialists. But some things are magic. With Cole out, today, the Yankees are putting the ball in the hands of their nastiest magician, sending him up against Yordan Alvarez, Jose Altuve, and the rest of the fearsome Houston Astros, and praying that he can pull a rabbit, or at least a five-inning shutout, out of his hat. It seems like a lot to ask, but you can’t predict baseball, and he’s done it before.

I’ll be honest, my main source for the Clemenceau stuff is this absolutely bonkers blog on the website of the Salvation Army from last December. The author, Dr Steve Kellner, applies Clemenceau’s insight to the need for new tactics in the battle against Satan, to keep up with his constant innovating. In this blog, I apply this insight to an even more urgent moral crusade: the 2024 Yankees.

Is cavalry on horseback redundant? I’m really out of my depth here but stay with me.

They prefer to be called general managers but it’s the same idea.

Joey Gallo, Aaron Hicks, Isiah Kiner-Falefa, Andrew Benintendi, Oswaldo Cabrera, Jake Bauers, Estevan Florial, Franchy Cordero, Willie Calhoun, Everson Pereira, I could go on but you’d get bored.

Team control in the MLB is about as sinister a concept as it sounds. Basically, all MLB rookies, no matter how promising they might be, are signed to six-year contracts. In the first three years, the player makes a fixed amount, somewhere between $700,000 to $950,000. Then, they have three “arbitration” years, where a player can go to a shadowy board of experts, who will decide how much that player should be paid next year. Usually, teams will reach an agreement with the players first, to avoid the awkwardness of the shadowy-board-of-experts process. Either way, the players invariably get paid much much less than a free-agent of similar caliber.

The Home Run Stroka!